Design And Performance Lab

|

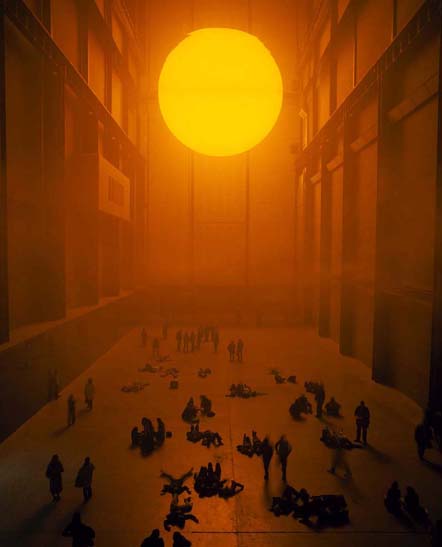

Transspatial Light and Virtual Choreography Johannes Birringer (c) 2004

It became an attraction to thousands of visitors who would linger under the atmospheric spell of light, lying on the stone floor, standing still or wandering about, sometimes as if following the internal cadences of a dance that transcended all logic. When I visited, there were solitary figures, couples and groups who spent hours under this light, silently gazing up at their pale reflections or - if seen from a distance - forming distinct patterns of movement, their contours in silhouette against the yellow fog. When I walked closer onto this crowded beach, the people seemed like dervishes who had stopped their spinning and were now lost in reverie. Perhaps unwittingly, Eliasson's work became an interactive movement installation. We hardly needed Merce Cunningham's company performing its "Event" there in November to realize that the space, under the transformative light, had become a stage. Not a dance stage in the sense in which Loïe Fuller's "danses lumineuses" transformed space through moving light sculptures created by her costumed body. Nor a proscenium on which a Robert Wilson or Saburo Teshigawara paint their abstract landscapes and carve mysterious paths of light into darkness. But a wide-open panorama, an immersive, perhaps even transcendental world of the kind the architects of Gothic cathedrals, 19th century painters of the sublime or 20th century light artists like James Turrell envisioned. In such immersive environments, the perspectival aesthetics of concert dance and the ways in which theatrical lighting accentuates dance's physical ephemerality are out of place. Light no longer serves to seduce the viewer into a preselection of images or to direct emotional response. Light quietly becomes a choreography of the virtual, enveloping exterior and interior spaces in silence, encompassing the emergence of continuous form in the behaviors of the "bewegte Betrachter." The Tate is no stage set and Eliasson's light is no lighing design, in any conventional sense. "Weather Project" creates a specific perceptual environment, similar to Turrell's Ganzfeld installations which allude to the scientific term for such uniform environments used for psycho-perceptual experiments where subjects are deprived of unnecessary sensory stimuli. Unlike conventional lighting design in the theatre, which distracts us by spotting, emphasizing or obscuring the dancers' bodies or by highlighting movement shape and contours against an abstract background of colored light, Eliasson's and Turrell's "total field" allows us slowly to become aware of our own heightened sense of space and the conditions of seeing, a slow intensification of our own kinesthetic experience - how we "give body" to a virtualized image-space. The "Weather" space was not fleeting and marked by intensities of the moment in which a dance becomes the place where it is and moves, but it was continuous light: hovering, thick, spreading, tactile, affluent, resonant. Such light, in its virtual choreography of any and all behaviors of the people who stepped inside, stimulates - over time - the many unspoken potentials and affects in our bodies. The uncanny orange quality of the light virtualized our bodies, so to speak. It suspended them in a paradoxical combination of stillness and movement, it made the space dimensionless, transspatial. My interest in environments of this kind is the result of working with digital media, image and sound projection, animation and interactive architectures for dance which changed my understanding of composition and choreography altogether, even though its historical precedents go back to Oskar Schlemmer and Lázló Moholy-Nagy's Bauhaus ideas of architectonic-spatial organisms. The emphasis has shifted from choreography to collaborative process, to the shaping of interactional design in responsive environments in which physical performance communicates with the environment to generate information. Dancing interacts with the virtual range of real-time computing which transforms images, sound, light, motion data -- the digital infrastructure of the communication that might include remote locations in a distributed network (telepresence). Since I did not have extensive lighting equipment at my disposal, I began to use a combination of natural and artificial light in my work, while also using digital video/film projection as sculptural dimension and light textures in the environment. The light of digital projection became plastic material in the Gestaltung of space and time. In this sense, digital environments take on the implications of Eliasson's "weather." I think of dance now as the opposite of the ephemeral whose precarious presence needed a special lighting spot to illuminate a leap or an extended foot. The specific leap or gesture in a responsive environment is not lost but tracked, recorded, sampled; it is never there for its own sake in the first place, but movements or gestures in my work are motivated by the environment and return to its processing of our actions. Interactive dance in a responsive, motion-sensing environment is always relational and recursive: it derives from an "ecological" consciousness. There is a historical connection between explorations of the site-specific and of everyday movement (in body art and dance since the 1960s) and current performance in virtual environments. The shift in our understanding of site specificity from the local to the virtual signals a concomitant shift from an anthropocentric view of dance to an ecological view in which the kinesphere is extended into nondimensional and intensive topologies of the digital. New technologies continuously extend our perception and proprioception. They place us corporeally and spiritually into relation with complex, emerging environments. Dance's intuitive strength of improvisation is naturally challenged by complexity, while continuous processing of movement-information lies at the core of the digital, if we see digital media as a new mode of framing sensory information yet containing an infinite number of possible permutations of the digital event. The role of light in the digital era is subsumed

by the functions and the aesthetics of image movement (image projection)

on the one hand, and by the more subtle convergent possibilities of

light and sound diffusion in the environment. In a responsive environment

where all areas of the space are mapped (via motion tracking) and our

movement generates sound, we don't have to design special lighting:

we can hear where we are. At the first laboratory on interactive media

in the former coal mine Göttelborn (2003), In the 60-minute telematic dancework "Flying Birdman" (2002), collaboratively created with performers in seven different sites in the United States and Brazil, the central medium is the live stream (video, audio, text, graphics, midi data) which links bodies with distant physical spaces. Telepresence creates interactive environments allowing the real-time synthesis of various media acting upon each other in a shared virtual reality (the internet) which needs to be spatialized through projection. In our studio the emphasis is on the dancer's actions, how she incorporates the projected light of the streaming images into her extended sense of the world, her extended body. The aesthetic challenge in telepresence is the conscious incorporation of the camera interface into the performance, with dancer and cameraperson working very closely together in a restricted area under subtly diffused light. The choreographic relationship to the streaming environment, and to the frame compositions of the virtual images created by the cameras, suggests that the dancer insert herself into a moving architecture and move "through" the filmspaces, becoming present in virtual space. A different approach was chosen by Carol Brown and her dancers in a recent media lab in Chelmsford, England. In their collaboration, Brown and digital architect Mette Ramsgard Thomsen devised an interactive environment ("SPAWN") to explore how kinetic information informs the behavior of virtual architectures. The dancers create duets or trios with the projected light of the architectures, and while their own bodily contours are tracked by the camera and processed by computer programs, they can affect the morphological shapes of the image-light and image-color. Their movement dynamics becomes embodied architecture. What I learnt from Robert Smithson's land-art is a certain dialectics of seeing, or perhaps it is a blurring, a contra-diction between site and non-site, natural landscape and processed landscape. Spiral Jetty was/is a site, somewhere in Utah, still evolving, the earth sculpture of the jetty disappearing and re-appearing according to weather and water levels of the Great Salt Lake. All I have seen are photographs. Associating site and image becomes stranger yet when one encounters a film of the "making," the choreography, ofSpiral Jetty. Returning to the same museum a few months later, a different film has taken its place, Lázló Moholy-Nagy's Light Space Modulator, an extraordinary abstract exploration of the colors black, white and gray, refractions upon refractions of light on moving glass (the Bauhaus "Glass Dance, "1929). The glass dance becomes light, a kinetic sculpture, a film: light-and-image-in-motion. This is dance which moves me. We live in the times of the digital earthwork, extenuation of conceptual art that links land and movement, material flow, entropy, emergence, and complexity, light and digital data, the natural elements and the theatre of interactivity. Virtualization - in digital media as in dance- is a quality of contemporary hybrid work, the means by which we bring the force of the virtual to affect our physical experience, directing our imagination from site to site, plane to plane, drifting rather than navigating. We change planes of contiguous reality.

Johannes Birringer is a choreographer and artistic director of AlienNation Co., a multimedia ensemble based in Houston (www.aliennationcompany.com). He has created numerous dance-theatre works, digital media installations and site-specific performances in collaboration with artists in Europe, North America, Latin America, and China. He is the author of several books, including Media and Performance: along the border (1998), Performance on the Edge: transformations of culture (2000), and Dance Technologies: Digital Performance in the 21st Century (forthcoming). After creating the dance and technology program at The Ohio State University, he now directs the Interaktionslabor Göttelborn in Germany (http://interaktionslabor.de) and the Telematics DAP Lab at Brunel University.

|